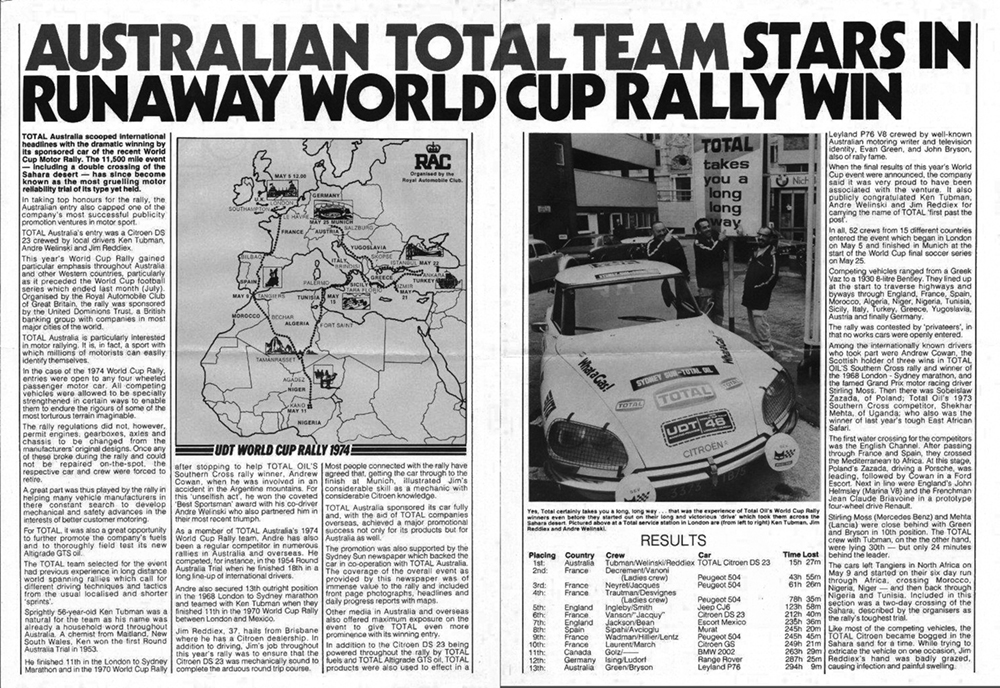

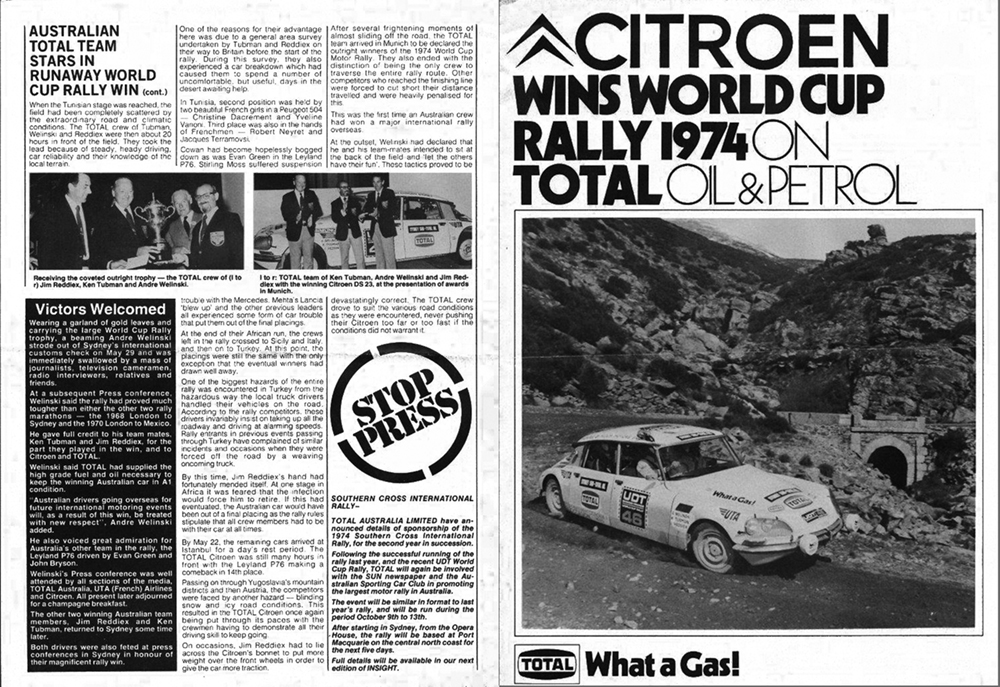

|

The crew

Andre Welinski (42) must deserve to be described as a regular

and enthusiastic entrant in these extraordinary long distance

rallies,

since he was the first person to apply for an entry in the 1968

Daily Express London-Sydney

Marathon,

the 1970 Daily Mirror London-Mexico World Cup Rally and this

last one,

the London-Sahara-Munich UDT World Cup Rally. A flamboyant

character,

he has a law practice in New South Wales, and interests in a

variety of

entrepreneur activities. Ken Tubman, the senior member (58) of

the team

has also run in all three events, like Welinski in another Volvo

in the

London-Sydney, and with him in a Morris 1800 in the

London-Mexico. He

is by profession a pharmacist, and has considerable rallying

experience, mostly in his home country, especially New South

Wales,

although there was an exploratory session in Europe. He won the

first

Redex Round-Australia trial in a Peugeot 203, which Reddiex says

“put

Peugeot on the map in Australia.” He had never driven a Citroen

before

last winter, when Welinski - who is a Citroen fan – lent him his

own.

Like most newcomers to these highly unusual cars, “Ken was most

unimpressed, finding it a great wallowing beast - not until our

survey

did he start to get some respect for it." Now he wants to buy an

SM.”

James Reddiex (37) is a newcomer to this, having done only four

previous local rallies, all in a Citroen GS. He did his

apprenticeship

with one of the only two Citroen importers in Australia,

progressing

with them until he eventually took over Maxim Motors of Brisbane

himself. So he is no newcomer to the apparent complexities of

the

D-model Citroens, and in the estimation of other

London~Sahara-Munich

competitors, his practical skill and experience is one of the

reasons

for the DS23’s success. Certainly that’s what both Andre and Ken

say.

Preparing the car

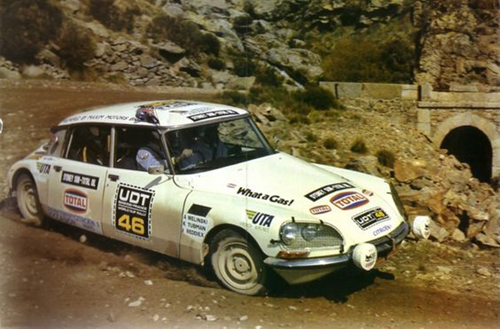

Car no. 46 started life as a standard carburettor-engined

Citroen DS23,

with unmodified 2,175 c.c. [actually 2,347 c.c.] four-cylinder

engine

supposedly producing its nominal 106 bhp (DIN) at 5,500 rpm

(maximum

torque l23lb.ft. at 3,500 rpm). Normal weight is 25.4 cwt at the

kerb;

weighed in London before the start, with the three standing on

the

weighbridge, and all tanks filled, four spare wheels but no

tools, food

or personal gear, the car scaled 36%cwt. “With 9 gallons of

water,

tools, spares, tucker and our bags I reckon it was at least two

tons.”

The carburettor engine was thought ideal. Perhaps

understandably,

Reddiex says “I’m a great believer in simplicity; I’m not

frightened by

the injection, but if anything goes wrong it’s difficult to find

the

fault without test gear—-all that really happens with a

carburettor

is it gets dirty, so you pull a jet out and clean it. Anyway, we

didn’t

feel that power and acceleration were the keynotes.”

“We ordered the car, and it was produced on l3 December last

year in

Paris. The only things that were non-standard as it came off the

line

were that we’d asked for no soundproofing (which saves about

1cwt), and

the Citroen competitions department had substituted on the line

top

suspension arms with splines cut to give 3cm (l.l8in.) more

ground

clearance in the normal height setting. In my opinion the

standard car

is about 1in. too low, and this is all it needs. The only other

'non-standard bits you can’t buy are the engine mounting

brackets; they

take all the acceleration and braking loads, and are normally

cast iron

; ours are steel, machined from solid.” Citroen in Paris have

not been

financially involved in this venture, but they did allow Reddiex

the

rare facility of building the car into its London-Sahara-Munich

form in

their competition workshop. This gave Jim access to a wealth of

rally

preparation knowhow.

A lower ratio final drive was used.

Citroen Safari rear suspension cylinders, slightly bigger to

deal with

the extra load, were fitted. There are not many rally winners

today

which rely on pressed steel wheels, but this one did, shod with

Michelin X 195/70VR 15in. steel-braced radial heavy tread tyres.

Tyre

pressures were to be varied between 28/26psi front/rear on

tarmac,

sometimes 33/26 on hard desert going, down to 7/28 on, or rather

in,

soft sand.

The other major suspension difference was in the damper

arrangements.

Damping of the still unique Citroen hydropneumatic system is

largely

controlled by simple pierced disc restrictor valves, one in each

suspension sphere. On current production cars, the valves (one

per

corner of the car) are pressed in. But at the introduction of

the

injection model, it had removable valves held in place with a

ring nut.

These were adopted here, three different sets being available to

vary

the damping according to conditions. There can be few

competitors who

could carry three sets of shock absorbers in a small plastic

bag, as

Reddiex could.

Each valve consists of a disc about the same size as a florin

but

twice as thick, pierced by four oblique holes. These apertures

are

partly covered on each side by shim-like washers rivetted to the

disc.

By varying the thickness and therefore the strength of these,

the rate

at which fluid will pass in bump and rebound is controlled.

Normal cars are more lightly damped in bump than rebound.

Competition

ones are the same both ways, but variously stiffer.

|

|

One of the few failings of the Citroen system is experienced

when one goes over a hump fast. The wheels are punched up into

the

arches, then as they reach the down side of the hump they drop

out

apparently unbraced ready for the descent of the body back on to

normal

height; there is an abrupt jerk, almost alarmingly abrupt in

comparison

with the car’s usual near-floating demeanour. By stiffening the

damper

valves, “you prevent the wheel going up so easy, and falling out

so

easy”, which does help a bit to correct this.

Brakes were left standard at the front, but with harder linings

for the

rear drums. The normal fuel tank (65 litres - 14.3 gallons) was

not

going to give enough range in the desert, so it was replaced

with a 120

litre (26.4 gallon) one, and another dorsal tank (65 litres) was

built

in behind the back seat as an auxiliary, with a changeover tap

on'the

back shelf, and two boot-mounted Bendix electric pumps to feed

the

normal mechanical pump if necessary. An extra fuel line was

fitted

running as a spare by a different route from the main pipe

straight to

the carburettor, by-passing the mechanical pump. Fuel on the

rally was

the required 98-octane except at Arlit, Agadez, Madoua and Kano;

they

tried to keep a supply of good stuff in the dorsal tank for use

whenever heavy going made pinking difficult to avoid. Patrick

Vanson’s

Citroen damaged a piston “probably I think because he had a

group 2

engine with a higher compression ratio” which didn’t like lower

octane

petrol. No manual distributor retard was used; instead they

changed

down whenever the going was very slow, keeping the revs up to

5,000 to

6,000 under lightest possible load.

An attraction of the DS for rough work is its very clean

underneath. It

is still vulnerable though, and by now Citroen know what needs

protecting. The normal front splash guard was replaced by 1/4in.

thick

reinforced steel one- “if I had to make it, it would have been

light

alloy, but there it was, on the shelf, so I used it.” The first

part of

the exhaust was protected with an 1/8in. plate; under the

five-speed

gearbox ahead of the undertray there was a little skid plate on

a

rubber block under the casing. The exhaust pipe mountings have

skis

too, and segments of 2CV tyres were stuck under the rear

suspension

boots to keep stones out.

The swivelling headlamps which are undeniably very valued by the

ordinary Citroen driver have proved distracting to rally drivers

sawing

at the wheel. Removing the cable swivel linkage, avoids that,

and also

with other detail changes makes removing the air chute and

getting at

the inboard front brakes much quicker. “Normally removing that

chute

takes 5 minutes; I can do it on our car in 15 sec.”

Drive shafts were removed and joints repacked with special

molybdenum

disulphide grease. All pipe runs were checked for chafing.

The survey

The car was finished in January, and by the time it appeared on

the

starting line at Wembley it had 8,200 km on its clock. Wisely

they made

a recce about a month before, buying the DS23 used by Neyret and

Terramorsi in the previous Rallye du Maroc, in order to look at

the

African part of the route.

“The great thing about the survey was we knew what to expect,

and that

it was rough for a very, very long way. Someone said to us after

one of

the Spanish special stages “Wasn’t that rough! I said “Boy,

you’ve got

a big surprise coming to you.” “Why?” ‘You’ve got a lot rougher

than

that in Africa and for a lot lot longer.” It’s only my idea, but

I

think that for a lot of them that didn’t go further than

Tamanrasset it

was because they were demoralised‚ they hit the desert at night,

they

got lost, they broke their cars when they did find the track; I

heard a

number talking that they were actually afraid of the desert.

Even when

we came back from Kano to Arlit there was so much dissension

about

going on to the desert at night that they gave us a five-hour

break to

wait until daylight - we were just as happy to do it in daylight

- but

there was a great deal of concern about the desert.”

How the car went

At Figuig (the Moroccan/Algerian border), they put on four new

tyres.

At Tamanrasset Airport Junction they topped up with half a pint

of

engine oil. There was a slight gearbox leak. And climbing

Assekreme

mountain (9,800 ft, one of the Hoggar group) they had their only

engine

stop, when in very hot early morning air fuel vaporised in the

mechanical pump, though the engine was not overheating. “I

poured water

over it, then put a wet towel on it, and we got going again.”

Back at Tamanrasset before heading south to Niger and Nigeria

they

spent 45 minutes attending to the car. Siafu Expeditions had

flown in

spares and tyres for several competitors including the Citroen.

The

crew fitted another set of tyres, and a set of sparking plugs.

One

lower pivot had been dragged off in sand; Jim cleaned and

replaced it.

The front height had gone down a bit, so that was adjusted, and

as one

rear damper valve was found to be cracked - they’d noticed it

softening

at the back – heavier ones were fitted all round. Brake pads

were

checked, brake linings cleaned and adjusted, the car was greased

and

gear oil topped up.

At Agadez a headlamp bulb had to be replaced, and a back door

hinge

tightened. At Madoua they had their first puncture.

Kano was a rest halt, and saw greasing, oil change, filter

change, a

new gearbox drain plug to cure leak from gasket, hydraulic oil

and

filter change, plugs and points re-set, and dust blown out of

radiator

core.

Before they end at the units themselves, the wires feeding the

trafficators have some unsupported length. That is why both had

been

broken, and had to be resoldered. From Australian experience,

Reddiex

knew that the right hand front suspension sphere, which is close

to the

exhaust manifold, can in continuously hot conditions fail in as

little

as 20,000 miles, so that was changed as a precaution. There had

been a

brief excursion off course, and an exhaust pipe bracket needed

straightening. They repaired the puncture and washed the car –

washing

the Citroen before controls if possible was part of their

strategy.

On the return north over the same very bad tracks between Madoua

and

Agadez, they broke up three tyres, and squashed the map lamp

bulb in a

door jamb.

At Arlit, the front height needing raising again a little, and

the air

cleaner element was changed as they‚had been through dust

storms.

Back at Tamanrasset, they replaced the lefthand front rebound

rubber

which was starting to go. They‚had lost a bolt out of a mudguard

bracket and the steering idler; these were replaced and “I just

tightened everything up.” Gear oil needed checking again, as

there was

still a slight leak.

From Illizi to In Amenas, one of the very roughest sections of

the

whole rally, they had another puncture.

At Tunis they gave the car another general service. A bonnet

lock

plunger pin had broken and was replaced. The right main beam

adjuster

screw had rattled out and was put back. Oil from the gearbox had

got on

to the front brake pads, which were only a quarter worn; still,

they

had to be replaced. “Pity, because I think we could have gone

the whole

way on those pads. “The rest of the front suspension rebound

rubbers

were fitted as a precaution. Three rear lamp bulbs were renewed,

and

the right front window had moved outwards a bit, so Jim

tightened that.

From the short Targa Florio stage to Messina they had another

puncture,

renewing both the set of tyres used and the four spares at St

Giovanni.

The final (7th) puncture happened in Turkey after Seban. At

Istanbul,

Jim greased the distributor cam which had squeaked; one new tyre

was

obtained from Mrs Patrick Vanson who was providing some support

for her

husband.

At Stavros in Greece‚- which was where Citroen service, hastily

mustered by the factory when they abruptly woke up to the fact

that

they had a possible -winner, first met them‚ - Jim mentioned

that he’d

noticed a slight rattle in the righthand front lower suspension

ball

joint on light bumps. It was this one whose protective boot had

been

torn off in the sand. Citroen changed the complete drive

assembly,

being the quickest thing to do, but for Jim it was “a

disappointment,

because I wanted to finish with the car as it had started.”

At the Yugoslav border with Austria, they adjusted the

handbrake-

”that’s all; and it’s not been touched since we finished.”

Driving conditions

Getting stuck in sand was something every competitor knew. The

Citroen

got stuck three times in the desert, the second time on the way

to

Arlit in Niger, when they slowed to see if they could help the

Peugeots

of Neyret and Mlle Dacremont which were bogged, and thus bogged

themselves. Normal procedure was to clear away sand in front of

the

wheels, put the suspension up to the third notch, let the

driving tyres

down to 7 psi, and drive out- That didn’t work, so they decided

to help

the Peugeots first. That didn’t go well; sand boards kept

skidding out

from under the rear wheels. Jim went back to the DS23, leaving

Andre

with Neyret and Dacremont, and cleared sand away from in front

of the

whole car, not just the tyres; it was while digging under the

Citroen’s

nose that he banged a hand which later went septic, briefly more

seriously than he admits. Asking Ken to “Just give me a little

push”

Jim started the car, and let the clutch out very gently; the car

stirred; calling the others over to push, they got the Citroen

out on

to a short stretch of hard stuff. Neyret’s car was closest, so

they

attached one tow rope to him, and he attached his to

Dacremont’s, which

was much further in. There wasn’t enough room for one pull; they

had to

go forwards 30 yards, go back, shorten the first rope, forwards

again,

and so on.

Was the Citroen much faster over the desert than the others?

Being in

front, they didn’t see much of others to compare. “But when we

all got

out of that, we packed up our ropes, and the Peugeots went on

and

waited for us a little ahead. We got going, approached them,

they waved

us on, then followed themselves, so that we had a small flying

start.

The next control was l06km further on, and we beat them there by

over

half an hour."

“We got bogged beside Mrs Trautmann; she had waved us on when

she was

stuck, we slowed, and down we went; Chuchua pulled us both out."

How much did conditions change between recce and rally? In

Morocco, the

Missour-Mengoub stretch had had big washaways and holes filled

in,

though it was still pretty rough; “our notes weren’t much use to

us

there. When we did the survey, the stretch from Hirhafok (near

Tamanrasset) north to lllizi was a nightmare. One bit was like a

lunar

landscape, we were driving over rocks trying to avoid bigger

rocks for

125 miles; it was worse than the corrugations, because you

couldn’t

avoid them; you couldn’t get going, having to zig-zag all the

time.

But, thankfully, it was gone for the rally; they’d graded it a

bit.”

“There were corrugations for roughly half the African part. The

worst

were between lllizi and In Amenas - 6 to 8in. deep and l5 to

l8in.

across the peaks. If you stopped on them, it was almost

impossible to

re-start. The whole car was dancing; you didn’t have double

vision, you

had quadruple vision. The only way was to put one wheel right up

on the

edge of the track; then you could beat the dance. The fastest we

went

in that stuff was 70 to 90 kph; we’d have liked to go faster,

but there

were washouts and (dried river) crossings.”

“Arlit to Agadez was badly washed out by rain before the rally.

On the

way down near Madoua the track was completely changed - sand had

washed

across, there were bad washouts, and sheets and sheets of water.

In

three days when we came back it had all gone - all dust again.

I’m told

that two hours after we left Kano they had 7in. of rain.

“Still on the way back to Tamanrasset, we hit a dust storm; we

turned

the driving lamps sideways to pick up the scrub, because you

couldn’t

see six yards ahead.”

Navigation

In Salah, in Algeria, will no doubt be engraved on several UDT

World

Cup Rally competitors’ hearts. It was a crucial moment in the

event.

Briefly covering something that changed the rally for many, and

which

took up more time than it takes to relate, a new tarmac road is

being

built southwards. It was not finished then (it won’t be for some

time)

and the confusion of bulldozer tracks at one point thoroughly

confused

the departure of the old piste which the rally had to follow.

Henry

Liddon says you could see in daylight how muddled it was from

the air;

but the competitors weren’t in the air, and it was night.

Reddiex says

that they eventually found the right piste; you had to go only a

little

way beyond on the correct side of some sandhills - we went

across on to

some very rough sand, and suddenly saw the track and then the

markers,

and we knew we were right. We turned round because we’d decided

we’d

all go together, and we put the spotlamp on Patrick Vanson,

waved it,

and took off and a couple of cars started to follow, and we just

assumed everyone would follow them. And it turned out that the

two were

Cowan and Chuchua.

Vanson told me later that he said to the others “Look,

Welinski’s gone

off that way and hasn’t come back – let’s go, but they wanted to

lie up

till daylight. He wanted to go, but on his own, and eventually

they

decided to follow and found the track. We worked out that we

couldstill

do the bit to Tamanrasset Airport Junction on time if we

averaged

ll0kph, so we streaked off and ended up 6 minutes late."

“It was probably only 1km radius, and the minute you got out of

it,

here was a thing saying Arak, and a good, well-marked piste -

but you

had to be on the track to find it.” They got lost once

more, near

Fort Gardel, but found themselves again in time.

Driving car no. 46

Autocar was privileged to be able to borrow the Citroen a week

after

the victorious arrival at Munich. They had driven it back to

Paris,

where someone had kindly bonked it slightly parking (not the

crew). I

collected it from Citroen Cars Ltd at Slough, and it seemed to

go as

efficiently as its astonishingly unbattered appearance would

suggest.

They had elected to run hot rather than dusty; the windows had

been

kept up in the sand, and the car was not nearly as messy as

usual,

though it had certainly not been vacuum’d. Instead of sitting on

squashy-marshmallows as one usually does in a DS, you are held

in an

equally comfortable but very much more locating bucket seat. The

car is

of course higher than usual, and so isthe seat. L can’t recall

driving

a car which corners as well and feels as stable in a fast bend

whilst

sitting in such an elevated position. Big Citroens always remind

me of

camels with frog noses; the camel resemblance is increased by

this

driving, position.

Everything feels most pleasantly free and run-in. It is also

noisier

than usual, the engine making a quite harsh, almost hammering

noise as

you rev it. It certainly is willing to rev, and to pull, though

you

realise that the car is heavier than standard. Gearing in fifth

seems

to work out at approximately l7 1/2 mph per 1,000 rpm, assuming

the

standard revcounter is accurate and checking the car over a

known

distance. There wasn’t time to check performance properly, but

it

certainly felt very fit. The column gearchange works with the

usual

Citroen precision. I had forgotten that it is easy to

heel-and-toe in

spite of that funny button brake “pedal”. The ride is not the

usual

near-magic-carpet one, but much stiffer at low speeds, almost

joggly -

it improves as you go faster. I couldn’t find a hump suitable to

see

how this DS behaved; but what bumps I did encounter did not

confuse it

in the least.

Probably because of the tyres, the steering felt lighter than

usual,

though it would still chatter at you if held on full lock when

manoeuvring. With the window down, a loud tyre whine is heard.

There is

quite a lot of bump-thump.

I coveted the American-made “Airguide” compass. Reddiex had said

how

they had tried a lot of compasses in a place in Paris, and had

been

horrified how many of them read differently. This big marine or

aeronautical one has been one of the few that seemed reliable,

and it

certainly had imperturbably dead-beat action. They found it read

correctly if nursed in the co-driver’s lap.

Under the bonnet one immediately notes that the normal spare

wheel

space is empty. This is to protect the radiator in any crash.

There was

certainly a fair bit of dust, and some oil still lying around

the

transmission. The normal radiator fan has an electric fan ahead

of it

neatly mounted in the cowling next to the core, and manually

switched.

I’ve been lucky enough to drive one or two rally cars after

they've won

events such as this, and including all three marathon rally

winners.

This Citroen is not as fast as the London-Mexico Escort -and it

might

be said to have avenged the misfortune of Lucian (sic) Bianchi

whose

Citroen crashed when leading the London-Sydney which the Hillman

Hunter

won - but it certainly felt the healthiest of all.

James Reddiex summed it up rather oddly but neatly. “The car

went

fantastically well - it went better than I hoped, but as good as

I

expected"

|