|

JM: Were

you aware that many Slough catalogues used reversed negatives of

left hand drive cars? I have a brochure for a vehicle with the

badge 8imA on the bootlid. And there are catalogues showing the

fuel filler on the nearside.

KS:

Everything was done on a budget. We continually had to justify

our existence to Paris. I have seen catalogues in English printed

in France using such reversed images.

JM:

As a VAT and customs duties consultant, I am all too aware that the

rationale behind setting up overseas factories was fiscal. High

levels of import duty meant that if production was undertaken locally,

the amount of duty was reduced.

KS:

In order to qualify for the label “Made in England’, 51% of the content

of the car had to be sourced in England. It was straightforward

to calculate the value of components but we also had to factor in

overheads – salaries, property costs and so on.

We also

exported cars to the British Empire countries where “made in England”

right hand drive was the norm and also to Belgium and

Switzerland. This had the advantage that duty paid on those

components imported from France which were incorporated into the

exported vehicles was recovered.

Paris was quite adamant that no ‘security components’ could be sourced

locally without their prior permission. With this approval, we

used torsion bars sourced from the English Steel Corporation on the

Light Fifteen but we had to demonstrate to Javel that security would

not be compromised as a result.

JM: Was this the rationale behind the ID

19 wooden dashboard?

KS:

Ah! the plank. No, it was not a “security component”. It

was a much cheaper solution than attempting to create a mirror image of

the French dashboard. Where the DS 19 dash was concerned, we made

a plastic mirror image version of the French nylon dashboard. We

had a wood mill in the factory which had been used for the Light

Fifteen dash and we had the expertise and this was the reason for the

ID’s walnut dash.

JM: I must admit

that I always though this slab of wood looked somewhat incongruous,

sandwiched as it was between the futuristic plastic air vents.

KS: The first version of this dash was

awful. Later ones where the top of the dash overlapped the timber

were much better.

JM: What was the reason for leather

upholstery?

KS:

I never liked leather. It is not a suitable material for

seats. The Sales Department was convinced that it was essential

to have leather trim in order to sell cars.

JM: Given that you are a vegetarian, is

this a philosophical objection?

KS:

In part but my main objections are that leather is cold in the winter,

hot in the summer and makes clothes shiny. I remember driving a

British Traction which was fitted with a leather front bench seat and

when cornering rather enthusiastically sliding across the seat.

Fortunately I let go of the steering wheel and the car stayed on the

road. The Sales Department had concluded that customers of the

Traction would want leather seats and a wooden dashboard and this was

carried forward to the ID 19.

|

|

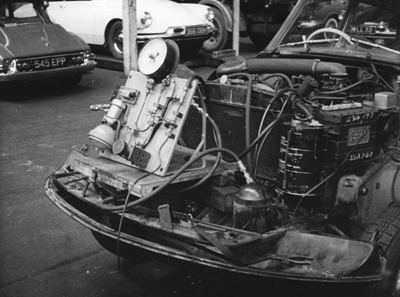

JM: Slough

D series cars were 12 volt from the outset whereas French cars used 6

volt electrics. What was Javel’s reaction to this?

KS:

They really didn’t want to know. I demonstrated the superiority

of the 12 volt system to them – better ignition, cheaper, easier to

assemble but they didn’t want to know… during the preparation of

the three right hand drive prototype Ds in 1955 at the rue du Théâtre,

I was informed by the Electrical Section that they had no budget for

the 12 volt, positive earth system and I must prepare it myself, which

I did. It worked at the first running test and our cars avoided

some of the electrical incidents that affected early French market cars.

JM: My

Dad had the voltage regulator fail on an ID 19 while on holiday in

France and he took it to a dealer who looked under the bonnet and said,

“Well here’s the problem. Some idiot has fitted the wrong dynamo!”

KS: That must have confused them…

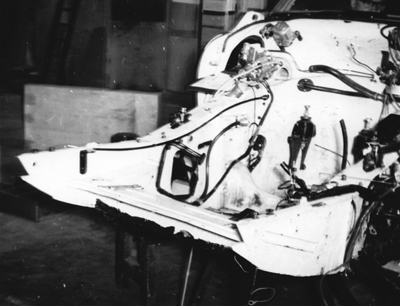

JM: Many Slough-built D Series used metal

as opposed to polyester roofs. Why was this? Were they

locally sourced?

KS:

No. They were all imported. We had problems with the

polyester roofs when it came to unpacking them. Even with four

people each holding a corner, a large number of them cracked.

JM: I know that the Décapotable

was never built in Slough but right hand drive versions were fitted

with many of the components – dashboard, seats, electrics, etc. that

were fitted to Slough models. Was this done in Slough or in Paris?

KS: It was done in Paris. We sent

them the bits.

JM: My Dad had a Slough-built DS19

Pallas. Was the Pallas trim locally sourced?

KS: The interior trim was sourced in

the UK.

|

|

JM:

Early IDs had an ‘upside down’ gearshift pattern compared to later

ones. Do you know why the change was made? Was this

anything to do with the different gearchange linkage required for right

hand drive?

KS: In fact early

French and British cars had the same pattern and when the change was

made in France, we did so too. The linkage made no difference.

JM: My father owned a Connaught ID and a DW.

Given the pas inventé ici (not

invented here) mindset at Javel, what was the attitude to these models?

KS: Connaught,

who were Citroën dealers, used to buy complete cars from us and convert

them. Although there was technical liaison between us, the

conversions were not officially sanctioned. As for the DW,

eventually Paris produced a manual DS. But they were not that

keen on our model.

JM: Slough anticipated the three

dial instrument panel that Paris introduced in 1968. Were they

concerned at this innovation?

KS:

after the first three or four hundred cars, the DS and ID were always

been fitted with round instruments. We could justify this using

the 51% rule.

JM: Which do you prefer, the BVH or BVM?

KS: I think I preferred the manual.

JM:

I always felt that the hydraulic change better suited the nature of the

car. One drove the DS with fingertips and toes, not arms and

legs. Later left hand drive IDs were fitted with a foot operated

parking brake but those destined for right hand drive markets retained

the handbrake. Why was this?

KS:

the engine was offset to the right in the DS. This was done to

allow access to components mounted on the left of the engine.

Since right hand drive had been envisaged from the start, it had been

contemplated that the engine be offset to the left for right hand drive

cars but it was decided that we would just have to put up with limited

access. This meant there was not enough room to fit a fourth

pedal in the narrower driver’s footwell; for this we were duly thankful.

|

|

JM: Since RHD production was envisaged

from the outset, what was your involvement?

KS: From

May 1946 I worked at the Slough Production Methods Department and this

meant I always had a great deal of contact with Paris regarding

adapting production methods from the large numbers built in Paris to

the much lower volumes envisaged at Slough. So when the DS was being

developed, management deemed it appropriate that someone from the

British operation should be involved at an early stage. And the choice

fell on me! Within the limits of complete confidentiality, I had

to find out all about the DS in all its details; to assess and acquire

compliance with all the British Road Traffic Acts, Construction and Use

Regulations, Vehicle Lighting Regulations and all other relevant Acts

and Orders; to assess the changes necessary in order to assemble, trim

and paint the vehicles at Slough. This was a vehicle which was

totally different from the Light Fifteen, Big Fifteen and Six

Cylinder. I had to become familiar with all the components,

units, assemblies and items in the car and to learn how they

functioned, in particular the hydropneumatic

suspension,

the hydraulically operated clutch and gearchange, brakes and steering

and to prepare a summary of components and materials for local purchase

before production could commence.From 1954, I spent 49% of my time at

the Bureau d'Etudes at the rue du Théâtre in Paris until shortly before

the launch of the DS at the 1955 salon. This meant I got to see all

sorts of ‘top secret’ studies.

JM: Can you tell me about some of these?

KS: Paul Magès

was a genius. He realised that high pressure hydraulics could be

used for many applications including window winders, windscreen wipers,

seat adjustment, cooling fan, dynamo and even transmission.

JM: Ah yes, the hydrostatic transmission

system. I am told it suffered from cavitation noise.

KS:

As was all too often the case, costs were what killed the idea. Paul

Magès had also developed an ABS system for the DS as early as 1955

along with anti-roll

suspension

where you could vary the body inclination from banking like a

motorcycle through a neutral, flat ride through to normal DS body

roll. Anti-roll suspension was first fitted to a 1955

Traction. The roll was controlled by electric motors.

JM: The idea of his that I really liked

was the one where the rear

section of the roof was hinged and was hydraulically raised through 90

degrees to act as an airdam to both improve braking efficiency and

increase the downforce on the rear wheels. But I am guessing that

costs were the reason this was never pursued.

KS: Yes, costs were always a problem.

JM: After

production at Slough ceased, UK market D series cars continued to be

fitted with Lucas tail and brake lights. Why was this?

KS: British

Road Vehicle Lighting Regulations again. The French lights were

not marked with the appropriate British Standards kitemark and it was

easier to continue to use the Lucas units until the European ‘E’

markings on the lamps were acceptable in the UK.

JM:

In the early sixties, my Dad had a car fitted with seatbelts – an

unheard of innovation. I remember arguing with him (as know-all

adolescents do) when he told me off for wearing the belt since this

indicated that I did not trust his driving. “It’s not your

driving that worries me, it is the other idiots…”

KS:

In 1960, we experimented with a four point harness. These were

fitted to our own cars. But the cost was too high so we developed

our own, three mounting harness. This will be the one fitted to

your father’s car. This was long before Volvo made a virtue out

of safety.

|