|

In 1970, Citroën launched two new models: the Maserati-powered

SM supercar and the far more modest but ultimately more

interesting and

influential GS. The vast majority of cars sold in Britain in

1970 were

utterly conventional, rear wheel drive vehicles with live rear

axles,

drum brakes and the aerodynamics of a house brick – cars like

the Ford

Cortina, Ford Escort, Morris Marina, Vauxhall Viva, Ford Capri,

and

Hillman Avenger. It is true that the Mini and 1100/1300

broke the

mould with front wheel drive. In mainland Europe, much the

same

held true although Renault and Peugeot built front wheel drive

cars.

Back in 1960 Citroën sold two ranges of cars. The D Series

which,

in Britain at least, was viewed as an expensive luxury car and

the 2CV

which was (wrongly) viewed as a primitive and agricultural

contraption. Between these two extremes, Citroën’s

competitors

had the marketplace to themselves. During the 1960s, the

Renault

4 was making inroads into 2CV territory and Peugeot’s 203 and

204 were

major players in Citroën’s domestic market. Citroën’s

response

was the Ami 6, the underpinnings of which derived from the

2CV.

The Ami 6 was always viewed as a stopgap product. The

Dyane was

introduced as a Renault 4 competitor.

Work started in 1960 on a project to fill this gap - the C 60 -

longer

and wider than the Ami but employing some of that car's styling

elements such as the reverse rake rear window and with a front

end

reminiscent of the DS, it would have been powered by a flat four

air

cooled engine of either 1,100 cc or 1,400 cc and the

larger-engined

version would have used hydropneumatic suspension. Development

costs

escalated and in 1963, the decision was taken to cut their

losses and

start a new project – a project which nearly brought about the

demise

of the company and which was indirectly responsible for the

Peugeot

take over in 1974.

Projet F (also known as Projet AP) was to have been the

definitive

middle range Citroën and was conceived in four versions using a

bored

out to 750cc version of the 2CV flat twin; flat four, air-cooled

one

litre;1600cc transverse mounted unit derived from the D Series

and a

Wankel rotary version, the latter fitted with hydropneumatic

suspension

while the other versions used torsion bars

While the use of advanced techniques such as front wheel drive

and

hydropneumatics had been enough to put Citroën at the forefront

of

automotive technology during the preceding thirty years, it was

felt

that something new was required if the company were to maintain

its

reputation. That something was the Wankel rotary engine

and a

joint venture was set up with NSU to build the

powerplants.

Unfortunately, the Wankel engine proved to be unreliable,

thirsty, and

very dirty (it would take another forty years until these

problems were

solved by Mazda) and there were problems with body

rigidity. The

two versions (torsion bar and hydropneumatic) differed in length

from

each other and the conventionally sprung vehicle suffered too

great a

variation in ride height between unladen and laden states and

there

were problems with road holding and handling. Additionally

there

was a considerable shortfall in refinement when the prototypes

were

pitted against the C60. Work on this project had reached

an

extremely advanced stage when Renault launched the almost

identically

styled 16 and to add insult to injury, the technique chosen for

Projet

F for welding the roof and door frames had been patented by

Renault. Citroën had decided not to patent the process

since it

did not want its competitors to have any inkling of what they

were up

to. On 14th April 1967, the project was dropped – presses

ordered

from Budd had to be paid for and millions of Francs were written

off.

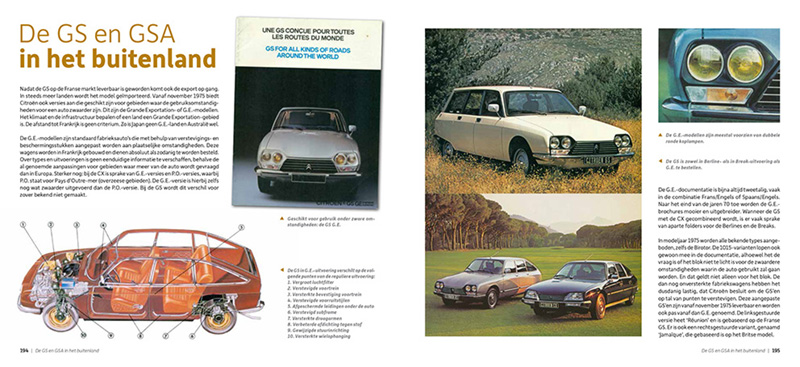

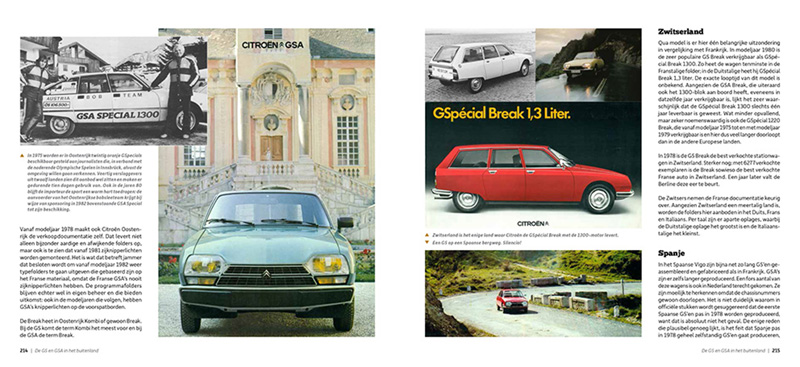

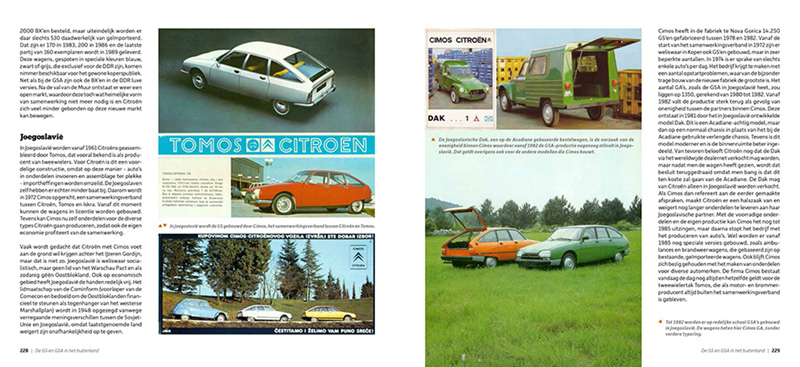

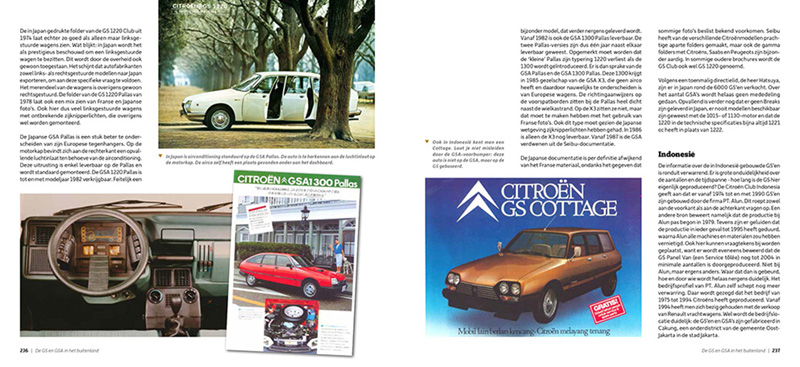

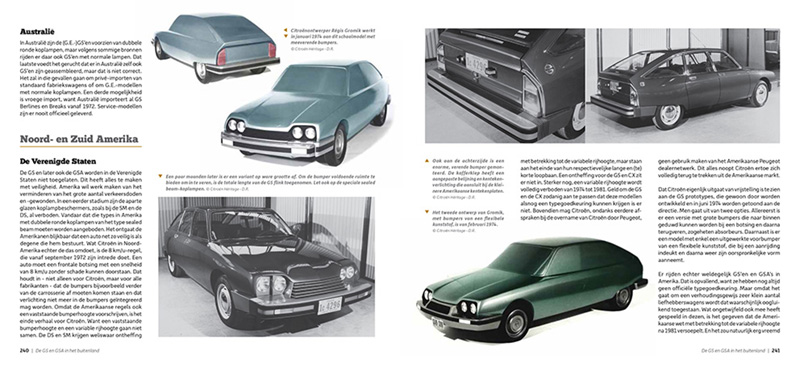

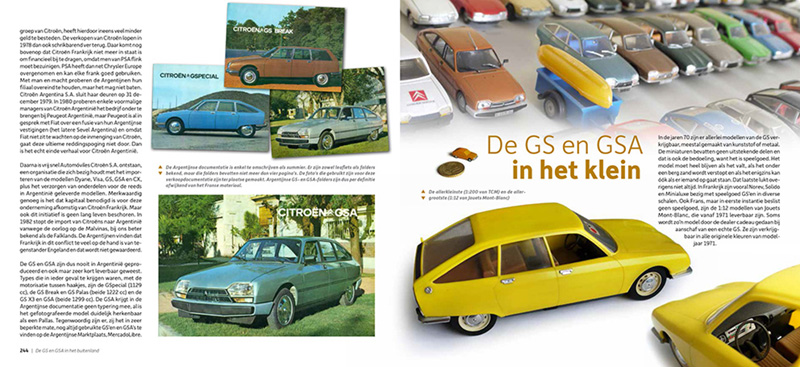

This book tells the incredible story of project G and its

predecessors

and how it was launched after only three years of development

and then

goes on to cover every variant of the car including the

Wankel-powered

Birotor and some lesser known vehicles built in Spain, Portugal,

South

Africa, the former Yugoslavia and Indonesia. It also

analyses the

car’s reception in markets outside France.

There are numerous hitherto unpublished photos of several

restyling

exercises from 1974 on and pictures of the development of the

GSA.

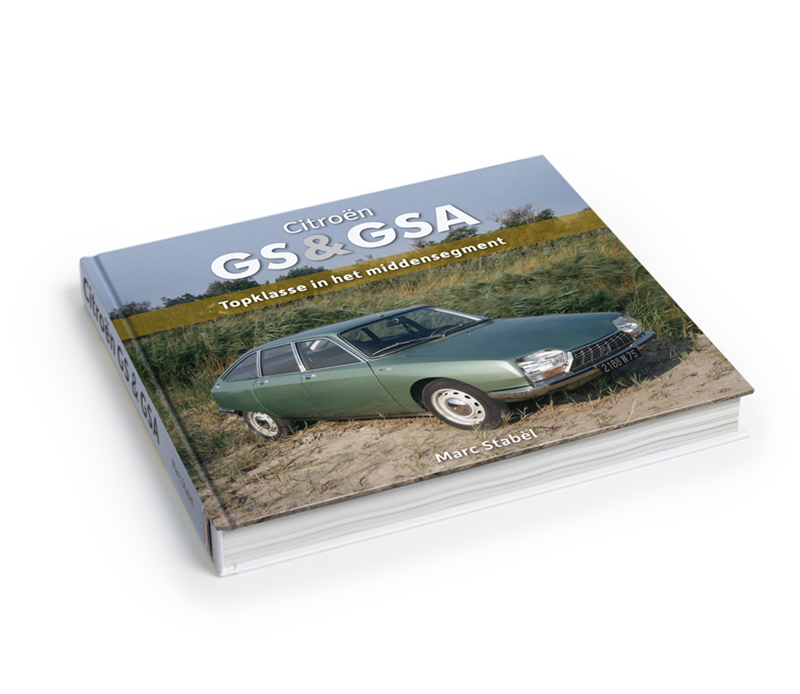

Inevitably this book will bear comparison with the only other

book

about the GS - ‘La Citroën GS de mon père’ by Dominique Pagneux

and for

most British readers, French is probably a more familiar

language than

Dutch but Stabèl’s book contains much more information and more

accurate information; is written with a passion that Pagneux’s

book

seems to lack; and contains a huge number of unpublished

photographs. I asked Marc Stabèl about this and he told me

that

in 2000, together with Martijn Kok he had already published a

book on

the GS & GSA since this model had been unfairly neglected by

motoring book publishers. A mere 450 copies were printed

(so it

is a collector’s item) and then, one month later, ETAI published

‘La

Citroën GS de mon père’. The Stabèl/Kok book looked rather

amateurish in comparison with its very small and almost

completely

monochrome pictures and unclear captions. It clearly could not

compete

with the full colour French book. This certainly cannot be said

for

this book which, although based on the 2000 book, has a

completely

different hardback presentation and full colour illustrations,

and

furthermore the content of the book has been hugely expanded and

amended where new information has been discovered over the last

16

years. When his old friend Thijs van der Zanden published his

Citroën

Visa book in 2010, Stabèl started toying with the idea of

revamping the

GS & GSA book and the result is yet another beautiful book

from the

Citrovisie Publishing house. Thijs was responsible for the

layout

and for many of the new pictures and information, thanks to his

contacts at Citroën. Martijn Kok was also involved at an early

stage

but had to withdraw due to other commitments.

I owned three G Series cars and for sheer driving pleasure, they

were

amongst the best Citroëns I have ever owned. They had

their

faults it is true: underpowered; thirsty; and a pig to work on

and then

of course there was the rust (although in this latter regard,

they were

no worse than their peers – just ask any Alfa Sud owner).

The car

was also a technological delight (as one discovered when working

on

them) so when Thijs told me that he would be publishing a book

on the

GS and GSA, I was really excited. The book fully met my

expectations.

About the author

Marc Stabèl, was born in 1961, is married to Irène, he has two

children

and lives in Eindhoven in the Netherlands where he teaches

English and

Dutch at a secondary school.

His passion for Citroën started in his youth, when his parents

decided

their Trabant 601 had become too unreliable and bought a

2CV4.

Five years later, their ‘Deuche’ was replaced by a GSpécial. At

the age

of 19, Marc bought his first car: a DSpécial. Just as I did, he

discovered that such a car is less than ideal transport for an

impecunious student so that experience didn’t last very long.

Eventually, after years of riding a bike, he bought himself a

GSA Club,

which he drove for some 12 years. After the GSA there have been

a BX 14

RE, a BX Break 16 TRI, a Xantia 1.6 Pallas and a Xantia Break

2.0 16V.

Currently he drives a C5 II Break 2.0 16V.

Once again, my only complaint is that the book is only available

in

Dutch. When I put this to him, he observed “…pictures speak

louder than

words. In which case you might want to cover your ears.”

Expanded edition now available in English.

|