|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

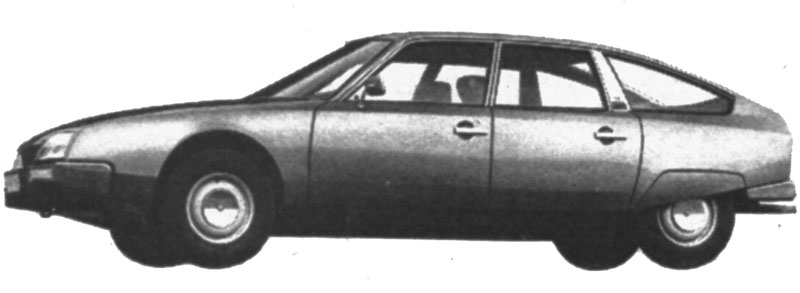

Medium-large car of great promise uses existing 2-litre engine in transverse installation. Well-tried hydropneumatic suspension, chassis reinforcement for unitary-type body, excellent aerodynamics. In production now for French market first, in Britain next year. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

CITROËN ARE unique in their devotion to advanced engineering. Each of their cars is designed to be ahead of its time, thus ensuring a long production run so that tooling costs may be amortised at a much lower rate than is general. This in turn means that despite their advanced features, the cars may be offered at competitive prices. Citroën succeeded first in the field both of very small cars - the 2CV and its enormous family of derivatives - and of large cars. They then turned their attention to the middle of the market and produced the GS, which was acclaimed just as the DS had been before it. The GS made the range much better-balanced, but a great gulf still yawned between it and the DS. This gap has now been at least partly closed by the introduction of another completely new car, the CX. Our table shows how much closer is the CX, in size and performance, to the DS than to the GS. This is inevitable given the decision to use the existing 2-litre engine as the basic power plant. The only alternative would have been to develop an entirely new engine, and this one imagines the company were in no position to do so soon after breaking new ground and investing heavily in the air-cooled GS flat-four. However, the CX is usefully smaller than the DS, which some people have always found a handful especially in town and in confined situations. Its wheelbase, though long by absolute standards, is shorter by 11in and this is reflected in the smaller turning circle. Disappointingly, it is hardly any lighter than the bigger car, but this is due to the much superior crashworthiness of the CX structure. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Main features

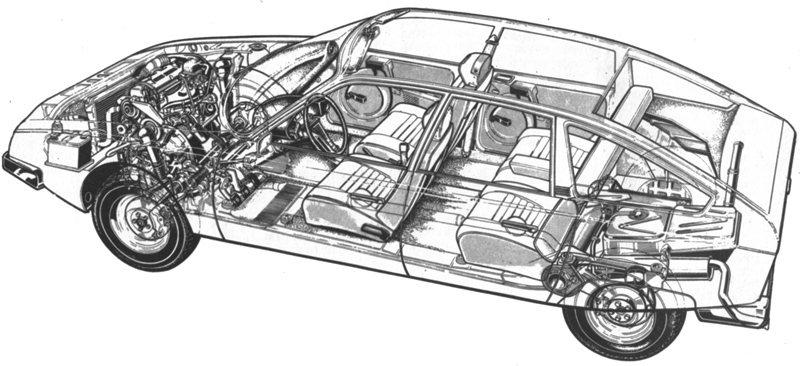

Although the D-series engine is used in the CX, it is turned sideways-on and inclined forward at 30deg to the vertical. The four-speed, two-shaft gearbox is driven via the diaphragm-spring clutch, its input shaft in line with the crankshaft centreline. Drive is taken from the inboard end of the output shaft through a massive helical spur to the final drive unit, which is therefore well off-centre (offset to the left as viewed from the driving seat). Rather than use drive shafts of unequal length, Citroen employ an intermediate shaft to take the right-wheel drive across the back of the engine, with a steady bearing attached to the sump. The wheels are smaller than Citroën have used before on a car of this size (or even on the GS), their diameter being 14in.; slightly larger-section tyres are used at the front than at the back, the spare being of the smaller size. Steering is by rack and pinion, the rack neatly tucked away behind the engine and thus very well protected in a frontal collision. Power steering, based on that of the SM but with less extreme gearing, is available as an option on all but the top model in the range, where it is standard. The suspension is Citroën’s well-tried hydropneumatic spring-damper units, with transverse arms at the front and trailing arms at the rear. At the front, the units act on the upper suspension arms, which are also linked to a massive anti-roll bar. The front suspension also uses anti-dive geometry. Disc brakes are used all round, though the transverse engine demands the use of outboard discs at the front, in contrast to previous Citroen practice. The front discs are ventilated. Brake application is by the same high-pressure hydraulic system which feeds the suspension with separate front and rear circuits and a proportioning valve operated by a small torsion bar from the front anti-roll bar. It is, however, the structure which is the greatest point of interest. In it Citroën have united a unitary body which is in itself very strong, with a longitudinal frame which ensures geometrical accuracy as well as transmitting crash loads, and affording better suppression of road and engine noise. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Citroën cutaway shows basic mechanical

layout with DS-derived 2-litre engine turned sideways and inclined

forward at 30deg. Hydropneumatic suspension units are clearly seen, but

the separate chassis is not evident in this view.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

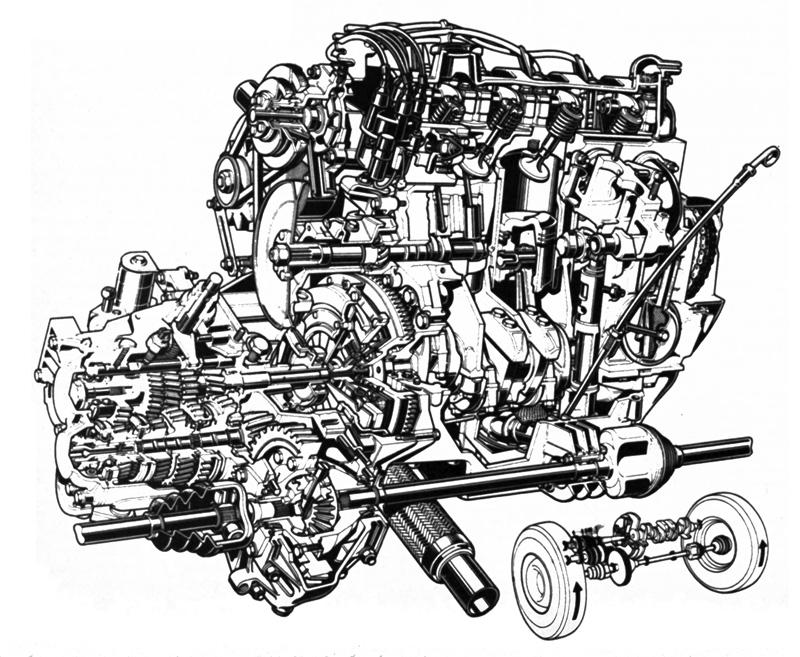

Engine and transmission Those who regard the Citroën 2-litre engine as old-fashioned forget that it was only introduced in 1966, to supplement and eventually replace the really old, long-stroke engine which dated back to before the war. It was a change which went almost unnoticed, yet the new engine was a great advance and is a perfectly acceptable basis for the CX power unit. Though it has no overhead camshaft, it is modern enough in other respects. The camshaft is high-set, rather as in the Hillman Avenger, and driven by a duplex chain. Short pushrods in a crossover pattern operate valves set in a 60deg vee - so the combustion chamber is hemispherical and the layout crossflow. In the CX the carburettor is mounted on the back of the engine, so to speak, while the exhaust is carried down the front face and through the gap between the sump and the final drive - another reason why the intermediate drive shaft, fixed relative to the engine, had to be employed. Skew gears from the camshaft drive the oil pump and the distributor, and a pulley on the opposite end of the shaft from the drive sprocket carries a belt drive to the water pump, and thence to the alternator. The fuel pump is mechanical, and a further drive serves the position-displacement hydraulic pump to provide pressure for braking, suspension and, where applicable, power steering. In its basic form, at 1,985 c.c., the engine is just over-square and gives an output of 102 bhp at 5 ,500 rpm. In this version the claimed maximum speed is 108 mph with the normal gearing, which is 19.3 mph per 1,000 rpm in top. This speed corresponds closely with peak power. There is also an economy version of the CX2000 with a higher final drive and also a higher top gear; in this case the maximum is a claimed 104 mph at a leisurely 4,600 rpm. The larger-capacity engine achieves its 2,175 c.c. capacity by boring-out, as in the D Super 5 of which it is also the power unit. For the CX2200 it produces 112 bhp at 5,500 rpm, giving a claimed maximum speed of 111 mph. The 2000 and 2200 share the same gearbox, though the 2200 uses a clutch of slightly larger diameter as well as a higher final drive ratio. As already mentioned, the gearbox is of two-shaft, all-indirect design; top gear is an overdrive ratio. The intermediate drive shaft across the back of the engine, a technique used also in the Lancia Beta, adds a certain degree of complication but at the same time avoids any possible problem of vibration of a long drive shaft and simplifies production in that the outer shafts, with one-piece joints inboard and constant-velocity joints outboard, are identical left and right. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Engine and transmission cutaway shows

crossflow engine layout, with exhaust taken beneath the engine from the

front face. Two-shaft, all-indirect gearbox and helical spur transfer

gear take drive to offset differential; an intermediate shaft takes

drive across the back of the engine with a steady bearing attached to

the sump.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Suspension and steering Though the self-levelling hydropneumatic suspension still seems an advanced concept to most motorists, Citroën point out that they have developed the system over 20 years, first on the D-series, and then on the GS. They have not only developed it to a high degree of reliability, but have also worked hard to eliminate some of its early, less desirable features. The anti-dive front end geometry is one result, helping the CX to maintain a constant ride height under braking and acceleration; the familiar ride-height adjustment is retained. Front and rear anti-roll bars are evidence of Citroën‘s determination to cut roll, which affects the handling even of the SM, to a practical minimum. In the CX, the front bar is nearly an inch in diameter, while that on the rear, connecting the trailing arms, is 0~69in. diameter. Although the wheels are smaller than those of the DS and GS, they are wide-rimmed. For both the 2000 and the_ 2200, the standard size is 5 1/2J-l4, with five-stud fixing. The tyres, remarkably, are different sizes front and rear, those at the front being of 185 section compared with 175 at the back (and on the spare). Quite why this was done is not clear; one is driven to suspect that bigger tyres were needed to achieve a sufficient load rating at the front, but that there was not enough room in the rear arches to clear 185 tyres – the rear arches are faired in for the sake of aerodynamic efficiency. Despite the smaller-diameter wheels, the CX brakes are very large. The use of 10 .2in. discs at the front, backed up by 9.2in. discs at the rear, indicate that Citroën have no intention of letting the CX run out of brakes in either its present or in future developed forms. The ventilated front discs are over three-quarters of an inch thick, and air is ducted to them to ensure cooling. Each front disc is acted on by two sets of pads, one operated by the main braking system with a separate piston for each independent hydraulic circuit; the other, smaller set of pads is operated by the parking brake lever. As in the DS, a pad-wear indicator is fitted, lighting a facia warning when the main pads are reduced to a certain thickness. Apart from the front/rear pressure proportioning valve already mentioned, pressure in the rear brake line is limited by a load-sensing valve on the rear suspension. Rack and pinion steering is used in the CX, drawing on all the experience gained with the DS and SM. The basic, non-powered system is relatively low-geared, with 4 1/2 turns of the wheel from lock to lock for a claimed turning circle between kerbs of 36ft. The steering wheel itself is an average 16in. in diameter. The powered system, offered as an option on all models and as standard on the 2200, is essentially that of the SM. It has the same self-centring and speed-related “feel” but has 2 1/2 turns from lock to lock instead of only two. The steering wheel is an inch smaller in diameter, and the servo unit has been isolated from the steering itself and installed in the passenger compartment. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

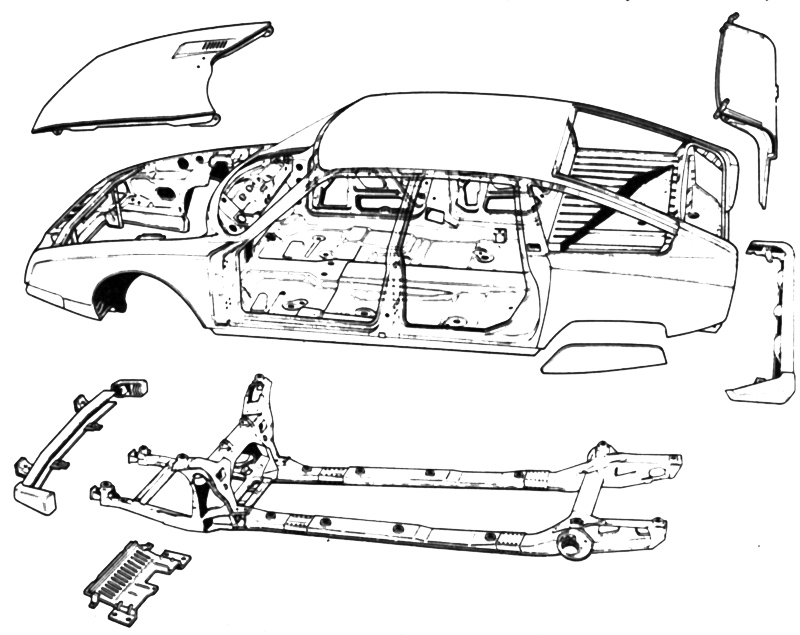

Structural drawing shows rigid body

structure, includes strongly caged passenger compartment. Separate

chassis, essentially front and rear subframes joined by two longeron

members, carries the engine and suspension units, and also mounts the

body on 16 flexible joints, Note the front end undertray.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

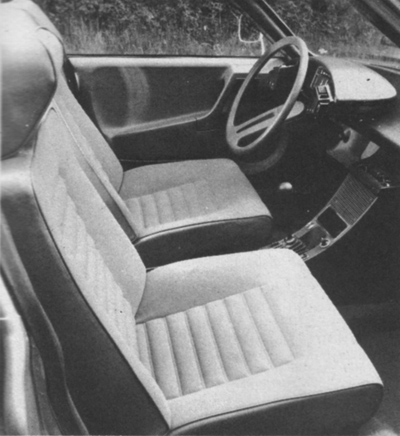

Structure The body shell of the CX, especially the passenger compartment, is as strong and stiff as those of many contemporaries. The main floor is a massive single pressing, to which are added cross-members for local stiffening in the seat-mounting areas, and which also give added resistance to sideways impact. The main sideways-impact strength, however, comes from the sill members which are box-sections of considerable size. They provide a footing for three very strong roll-over hoops formed by the main pillars of the six-light structure, which in turn form a complete “cage” by linking up with the roof side rails which run in a smooth arc from the windscreen base to the extreme rear of the fastback-styled body. At the front of the passenger compartment, a single bulkhead pressing crosses the structure; at the rear, a second diaphragm isolates the boot and its contents, ensuring that luggage does not burst into the passenger compartment in a severe frontal collision. Citroën’s engineers presumably started with the idea of using front and rear subframes to obtain better engine and road noise insulation, but the idea was taken one stage further. In effect the subframes are there, but they are linked beneath the body by two longerons which complete a chassis frame to which the entire body is mounted by sixteen flexible couplings. The longerons are wide but not very deep, so the chassis is not particularly strong in torsion; but it does resist any tendency to “lozenge” in a horizontal plane. This ensures accurate suspension geometry and improves the handling; while body and chassis together are quite adequately stiff in torsion. The chassis performs two other functions. It is a noise filter, and also the first line of defence against front or rear impact. Because the engine/transmission and the suspension are mounted to the chassis, mostly by carefully-designed flexible attachments, and the body is then flexibly mounted to the chassis, both engine and road noise has to pass two barriers to reach the interior. The front part of the frame is the most massive of all, the longerons being joined by two cross-members, one close to the extreme front and the other just forward of the passenger compartment. An arch-frame is built up on this second cross-member, with outward extensions at the top to house the front suspension units. The engine sits immediately ahead of the arch, attached low down by flexible couplings and high up by two massive steady-bars picking up on built-up brackets. The front anti-roll bar, and the steering rack, pass behind the arch-frame and the suspension link attachment points are housed within it. The rear subframe is much simpler. The longerons are continued rearwards, becoming much deeper to provide protection for the fuel tank which sits between them. The single cross-member is a very large tube, to the ends of which are attached the rear suspension trailing arms. While the front hydropneumatic units are housed vertically in the arch-frame, those at the rear lie almost horizontally, nested within the deepest section of the longeron. The front and rear bumpers are, naturally, attached to the extreme ends of the chassis frame. While they are not claimed to be American-style 5 mph bumpers, there is no doubt they could be made so with little extra effort, since the second function of the chassis frame is to transmit and absorb the first force of any front or rear impact. Because it is a continuous structure, it is able to distribute loads widely, while keeping them clear of the passenger compartment. Once the impact exceeds a certain severity, the compartment does of course become involved, but by that time the frame and then (in a frontal accident) the engine/transmission assembly will have played their part in absorbing loads and reducing the deceleration. Citroen claim that after a 31 mph crash into a barrier at 60deg angle - a more difficult case to meet, in many ways, than an absolutely “square” collision, and also perhaps more realistic - three of the four doors could still be opened. Aerodynamics and Equipment It is depressing to spend too much time talking about the crashworthiness of a new car, for crashing is not after all its prime function. Safety is a good thing to have, but it costs weight, and weight costs money and economy. Citroën have done their best, as always, to regain as much as possible by seeking to design the most aerodynamically efficient body consistent with practical requirements. All the hallmarks of proper aerodynamic design are there. The nose entry is smooth, the headlamp lenses blended into the contour. A smooth under-tray attached to the bottom of the chassis frame runs back as far as the front axle line. The windscreen is steeply raked and also curved, but it is interesting that Citroën have not seen fit to do away with conventional gutter rails. At the rear, there is a distinct break where the roof ends, and the rear window is concave, as is the (very short) upper deck of the boot lid. The lid curves smoothly over and is then undercut slightly to provide a number-plate housing. The rear wheel arches, but not the front ones, are faired; the 2200 also has wheel trims which virtually turn the wheels into plain, flat discs. The result of all this, and of attention to detail in such things as sealing and exterior door handle design, is a claimed drag coefficient of 0-30, a figure unrivalled by any large saloon other than Citroën’s own DS. Low drag does not of itself guarantee exceptional fuel economy, as Citroën themselves proved with the GS; but in alliance with sufficient power and high enough gearing it promises a substantial advantage. Given the very long wheelbase, it is not surprising that there is plenty of room inside the car. There is no evidence of the back seat design being skimped, either in cushion size or in the rake of its backrest. The CX is a full four (or five) seater in every sense of the word. The boot, too, is large and very reminiscent of the GS, being an almost perfect box-shape with no sill at all. The spare wheel is stowed under the bonnet, and needs to be removed to gain proper access to most engine components; but once it is out, access is certainly much easier than in the DS or the GS. Inside, all the instruments and minor controls are grouped on a binnacle which looks for all the world like a small, sectioned flying saucer hovering above the rest of the facia. The switches ranged round its edge are all within finger-reach of the steering wheel rim; the indicators, in Citroën tradition, are not self-cancelling. Because of the limited space in the binnacle, Citroen have retained their drum-type speedometer rotating behind a magnifying porthole, as used in the home-market GS. The same arrangement is also used for the rev counter where one is fitted. Other instruments comprise a clock, fuel gauge and voltmeter. The only water temperature indication is a warning light. A centre console carries other minor controls, including those for the heater. The heating and ventilation system is of the true air-blending type, with a permanently-hot matrix. One very noticeable feature is the use of a single very large wiper blade, centrally pivoted, sweeping the whole screen. This gives a simplified system, while Citroën claim that since the blade is always parallel to the airflow over the screen, there is no risk of lifting-off. The front seats, which move fore and aft through a range of 220mm (over 8 1/2in.) have reclining backrests. The driver’s seat is adjustable for height, though not on the move, but head restraints are offered only as an option. Where the optional inertia-reel belts are ordered, they are (for the French market,at least) neatly concealed within the centre door pillars, the reels at the base. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Production and Development

The CX is now in production at the new Citroën factory at Aulnay near Paris, which opened only recently and “cut its teeth" on a small run of the DS. It will unfortunately be some time before the British motorist has a chance to buy the car, since right-hand-drive production is not scheduled until late spring of l975. While the CX is for the time being available in only three very similar forms -2000, 2000 Economy and 2200 - there is clearly scope for considerable development. The engine could easily be uprated to the standard of the 2.3 litre Pallas, with or without fuel injection. A five- speed gearbox, however, is unlikely because a fifth speed would add to the width of the engine/transmission package and there appears not to be room. Undoubtedly, work is going ahead on an automatic transmission for the CX, to be offered as an option. The front-drive layout of the car lends itself to alternative body styles, of which an estate - the CX Safari? - is the most obvious. Like the DS Safari, it would offer considerable volume and easy loading. At the time of the introduction, the price of the CX had not been decided. Since it is a smaller car than the DS, it will presumably sell at a lower price; but since it embodies more advanced engineering, that price may not be much lower. There remains the question of what will eventually fill the gap which still exists between the GSl220 and the CX2000. It cries out for a car of 1,500-1,600 c.c., and the eventual answer may be found in the form of a GS with a bigger engine. As to where that engine may come from, one should perhaps consider the implications of the recently-announced agreement between Citroen and Peugeot. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Driving impressions Europe these days is getting to be a difficult place to launch a new car without attracting a blaze of local publicity. Citroën took their journalists to Swedish Lapland, there to face a wide variety of roads, the unpredictable nature of the reindeer and the sadly, wholly predictable attitude of the mosquitoes. My driving started with the plain 2000 (the Economy version not being available), with a half-way change to the 2200. The total route covered some 260 miles in a loop from Gallivare, north and then east to the Finnish border and back. The roads varied from semi-sealed Swedish country track to fast, modem trunk road. The immediate impression of the CX was that it was an easier car to get used to than the DS, or even the GS. All the controls feel more conventional - especially the brakes, which do not operate in the same load-sensitive, no-movement manner as in the earlier cars. One could very quickly drive with confidence, and no feeling of strangeness. The next very firm impression was one of comfort and stability. By any standard, let alone that of the older Citroëns, the CX rolls very little and feels a great deal more predictable and reassuring as a result. If the firm control of, roll has affected the ride, one is scarcely aware of it. In fact the ride feels slightly harsh at low speed on bad surfaces, but that is the only loss. At higher speed there is no sign of the “float” which afflicted the DS in its early days, and reaction to single sharp humps and badly-spaced undulations, while still marked, does not have the sometimes-spectacular violence of the bigger car. Again, one might have expected 4 1/2 tums from lock to lock to make the steering feel uncomfortably low-geared, more so on a route which included many tight corners, some of them entered while braking down from high speed. Yet at no time did I feel unable to apply lock as quickly as I needed it, except when doing a three-point turn in a fairly narrow road. For the most part the CX’s handling is remarkably neutral for a nose-heavy, front-drive car. Certainly the understeer increases if corners are taken very fast, but one expects that and the behaviour is always predictable. On a loose surface, the tail will readily drift outwards and in this case the movement is easier to control with the throttle than with opposite lock. Inevitably there is some reaction to sudden opening or closing of the throttle, but much less than in, say, a BLMC 1800. The engine feels entirely different from the great mechanical lump it seems in the DS, partly no doubt because it is farther away and partly because of the way it is mounted. The chassis succeeds less well in damping out road noise, which is still noticeable at times on most surfaces. Because of the quietness of the engine and exhaust, the performance seems less than spectacular. Citroën actually claim a time of about l3sec to 60 mph for the 2000, and about ll.5sec for the 2200, but we had no chance to verify these figures more than very approximately. But the claimed maximum speeds seemed to be about right, if not actually modest. The 2200 would hold an indicated 180-185 km/hour (112-115 mph) for long periods, even on slight gradients and through bends. Though the engine is over the power peak at maximum speed, there is no sign of any falling-off of power, no valve- bounce or sudden strangulation. The 2200 in particular was driven very much on the rev-counter, and I found the Cyclops-eye type of instrument much better as a rev-counter than as a speedometer. I am more -than ever convinced, after driving the SM and now the CX, that steering can be over-geared and too responsive for the average driver. The effect is much less obvious in the CX, but I am inclined to think three tums from lock to lock would be a better compromise between ease of control and rapid steering response. In other respects the system has much to recommend it, especially the servo-centring. During the drive it rained considerably, giving a chance to try the single-wiper in earnest. Citroën’s anti-lifting claim seems well justified, though the blade appears to leave a large unwiped area at both top corners of the screen instead of just one as would be the case with a two-blade system. The CX is generally a quiet car, although some wind rush is added to the degree of road noise already referred to, so perhaps the gutter rails do play a part. When a side window is opened, the noise becomes spectacularly worse, so it is as well that the new ventilation system is so good. The seats, upholstered in nylon, proved excellent except that I felt a slight lack of lumbar support after four hours. I also tried riding in the back, and was very impressed by the comfort there: since I am well over six feet, this is something I find all too rarely. As for economy, the 2000 (which was taken on by somebody with less regard for fuel consumption) achieved over 27 mpg, which must be regarded as good on an exercise of this kind. The 2200 which was driven much harder both by the first incumbent and by me, still managed 24~5 mpg which is, relatively speaking, even better. There can be no doubt that the CX, the second big European car to be launched since the fuel crisis, is as well placed as anything in its class to make good use of precious fuel. In other ways it marks a considerable advance for Citroën. It is less idiosyncratic, easier to drive (without, as far as one can see, sacrificing any of the traditional Citroën virtues) and much improved in handling and mechanical noise. The bold decision to use a transverse engine installation in a car this size has paid off well in terms of safety and use of space, and the CS must surely succeed in winning the favour of a large part of the European middle-class market. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

© 1974 Autocar/2011 Citroënët

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||