Technologies abandonnées |

|

|

Throughout 2015, there were rumours that Citroën has decided to abandon hydropneumatics (the C5 Crosstourer would seem to be the final iteration of this system). In 2014, the Citroenian published a piece I had written on abandoned technologies and this piece is based on that article. Since Peugeot took over the company in 1974,many of the core technologies that defined Citroën have been abandoned as a result of enforced ‘banalisation’ of the marque. In 2007, I was employed as a consultant for Citroën UK’s ‘Different Is Everything’ marketing campaign and I was asked to come up with a list of ‘Citroën Firsts’. For the UK company, this represented something of a U-turn. In a bid to reinvent itself, the company had determinedly ignored its past - that is until the C6 was launched. Here was a car that drew upon the technological inheritance of its forebears and, directed no doubt by the Paris Head Office, they decided to look back at their heritage. The trouble was that in a Stalinesque rewriting of history, the company archives had been purged and there were few people left in the company who could remember the pre-1974 glory days. Which was why I was brought in.

|

|

|

Ian Hughes, Marketing Director at Citroën UK wrote a foreword to the Different Is Everything book:

But working on this project - looking up our company's history, has had a quite different outcome. We have discovered so many incredible facts about André Citroën and his followers through the years that it has genuinely made us proud to say we're a part of the Citroën organisation. |

|

|

André Citroën thought in a different way from everybody else, it's as simple as that. It wouldn't be an exaggeration to say that he was maybe one hundred years ahead of his time. He was responsible, almost single-mindedly, for putting ordinary people right across Europe into motor cars. Where an industry didn't actually exist, he created it: car dealers, part-exchange, car finance, marketing and international sales operations. In his factory he built a crèche and hospital and had both a subsidised canteen and shops, typical of today's caring management, but unthinkable in 1919! The company went on to innovate in

so many ways that 21st century

motoring is still based on one of its earliest successes; with its very

many advantages, front wheel drive is now almost universal -

Citroën

conceived the first ever mass-produced car with this configuration with

the launch of the Traction Avant in 1934. This wasn't thinking differently for the sake of it, it was an inquisitive and analytical mind-set and the results were astounding. It's a philosophy we still practise today, as our current and upcoming models so clearly prove. |

|

|

My list of 'Citroën Firsts' covered the obvious –

My list also included ‘firsts’ which I thought were important

in the

history of the automobile such as:

The DS was okay although the ‘total car’ aspect of centralised hydraulics was quietly ignored. The Traction was safe since that all happened long ago and British comedian Jasper Carrot hadn’t made a career out of mocking it. |

|

|

So, let’s start with the A Series. My list comprised: |

|

|

|

|

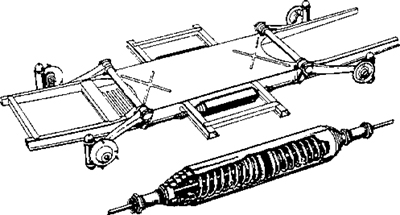

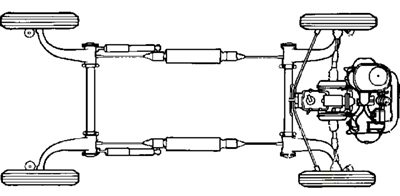

• Inboard front brakes One advantage of this is that it reduces the unsprung weight (and therefore the inertia) of the suspension. Another advantage is that this allows centre point/zero-offset steering whereby the pivot point of the steering (the vertical axis around which the front wheel rotates) runs through the centre of the tyre’s contact point with the road. This leads to very precise and accurate steering and furthermore, ensures that in the event of a front tyre blow out, the car remains on course and can be steered and braked to safety. Inboard brakes were not confined to the A Series of course. The D Series, SM, GS and GSA all made use of them. However, with the introduction of transverse engines, (from the CX on), there was insufficient room for inboard brakes or for centre point steering. • Front suspension geometry whereby the wheel leans over therefore ensuring that when body roll kicks in, the wheel remains perpendicular to the road surface. • Anti-dive front suspension geometry whereby the lower pivot point is mounted forward of the perpendicular – under heavy braking, the car body is forced upwards. This geometry was used in all models up to those fitted with MacPherson struts. • Parking brake operating on the front wheels – this has the great advantage that it can be used as a very effective emergency brake. The disadvantage, when coupled with disc as opposed to drum brakes was the risk that the car would roll away if the brake was not firmly applied when parked on an incline. This was caused by the discs cooling and contracting. • Yoder hinge – used for the 2CV bonnet and bootlid. I suspect that increasingly stringent safety regulations were responsible for the demise of this invention. |

|

|

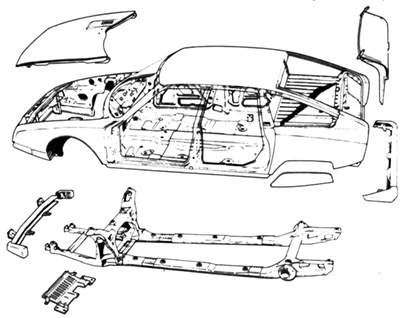

I then turned to the D Series and the list included: • Centre-lock road wheels – I would imagine that these were abandoned since many tyre outlets did not have the appropriate machinery to allow them to balance the wheels. • Single-spoke steering wheel – this was effectively killed off by the need to fit an airbag in the steering wheel. • Directional headlamps – discontinued and then subsequently reintroduced after the competition re-invented them. • High level rear indicators – this item was retained by Citroën UK – somehow the marketeers made a connection between them and the boomerang rear light cluster of the C6 – they were both ‘unusual’: never mind that the D’s lights were far more visible than indicators mounted in a lower and more conventional location. • Removable panels bolted to a skeleton frame British car manufacturer Rover adopted this type of construction for its P6 model in 1963. • Lightweight ‘plastic’ body panels – initially used for the roof in the DS and later used on the Méhari (for the entire body) and AX and BX to reduce weight and thereby improve performance and economy. Again, it is likely that safety regulations bore a large part in the death of this idea – although current cars do use plastics for some body panels such as bumpers and grills. • Centralised hydraulics – as mentioned above, this was a ‘total car’ solution; elements of which were abandoned, starting with the steering in the BX and subsequent models and then moving to the brakes. In Citroën marketing speak, this is a ‘decentralised’ system when it is confined to the suspension. From a purely economics perspective, it makes sense to build cars from a common parts bin. At the time, Citroën claimed that there were concerns about powering the brakes off a central high pressure hydraulic system should the engine die. This is, of course, complete nonsense since the brakes have their own accumulator which provides power for the brakes in such circumstances and once that reserve is exhausted, the suspension pressure can be used. • Mineral-based hydraulic fluid – far superior to conventional brake fluid which is intensely hygroscopic. |

|

|

• Articulating union (D rear brakes) This was developed at a time when conventional flexible tubing could not withstand the very high pressures used in the Citroën hydraulic system. A swivel was mounted on the rear suspension arm in line with the middle of the suspension arm bearings so that it could rotate with the arm in the bearings. The output half of the swivel was fixed to the suspension arm and moved with it while the input side had an arm which was anchored to the chassis, keeping that side stationary in relation to the chassis. The input side was of a larger diameter and fitted over the end of the output side with O ring seals between them and a dust seal over the join. An aluminium cap finished off the outer end and kept dirt away from there. When the brake is applied, fluid enters the pipe through the outer housing into the space between the outer and inner housings. There is a shallow groove in the inner housing that creates this space and an O ring on either side of this groove, mounted in their own grooves in the outer housing, which prevented the fluid from leaking. The inner housing had a hollow centre and a hole from the shallow groove into this allowed the fluid through. The inner housing had the output pipe attached through the side of it and the fluid can therefore flow straight into the pipe and thence to the brake cylinder. |

|

|

• DIRAVI Moving

on from the DS, the SM introduced the world to DIRAVI which is an

acronym for "Direction à rappel asservi" (steering with power assisted

return") which was marketed as VariPower in the UK and SpeedFeel in the

USA. This was a fully hydraulic ‘steer by wire’ system with no

direct mechanical connection between the steering column and the

steering rack during normal operation although a mechanical connection

would be established in the event of a loss of hydraulic

pressure. It provides automatic return to the straight ahead

position whenever the engine is running. The centring force

varies in relation to both vehicle speed and steering wheel

deflection. The system requires minimal physical exertion and is

a delight to use once one has got used to it. It allows for very

high ratio (and therefore fast) operation with only two turns from lock

to lock in the SM (2.5 in the CX and 3 in some LHD V6 XMs). Front tyre

blowouts, potholes, and other road surface irregularities cannot affect

the steering since the direction of the steered wheels can only be

changed by steering wheel input. |

|

|

• Hybrid chassis/body The CX was fitted with a hybrid chassis/body arrangement whereby the front and rear subframes were connected and the bodyshell was mounted on noise and shock-absorbing mountings. |

|

|

|

|

• Air-cooled boxer engines Over the years, Citroën experimented with alternative engine configurations, starting with the horizontally-opposed twin cylinder that powered the A Series. A horizontally opposed six cylinder was proposed for the D Series but was too thirsty. A four cylinder unit was developed for the GS, GSA and Ami Super but this suffered from noise since, being air-cooled, it lacked the sound damping effects of a water jacket. It was also thirsty and suffered from a relative lack of power. My C6 V6 diesel returns better fuel consumption than my 1015cc GSX managed. |

|

|

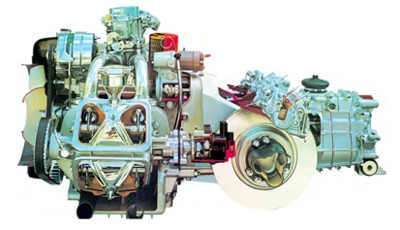

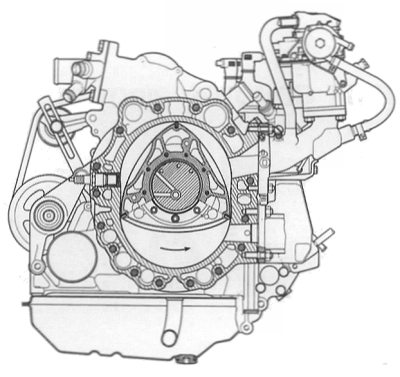

• Wankel rotary engine Citroën co-developed the Wankel rotary engine with NSU but as was all too often the case with Citroën, there were insufficient funds to develop the concept and overcome its shortcomings of excessive fuel consumption and emissions, not to mention the rotor tip wear problems. Mazda who stuck with the idea have been successful but the vast majority of their cars use conventional engines. |

|

|

|

|

• PRN satellites PRN (Pluie = Rain, Route = Road, Nuit = Night) satellites were first seen in production in the CX although they were first proposed by Michel Harmand in the stillborn Projet F in the nineteen sixties. Early versions of the Visa, the GSA (although on early UK versions of this car, the old GS set up was used) and Oltcit Axel and early versions of the BX used this highly ergonomic answer to the proliferation of switches and stalks that required twisting, pushing and pulling that were fitted to the majority of other manufacturers' cars. All the controls were logically grouped around the steering wheel thereby allowing their operation without having to remove one's hands from the wheel. Notwithstanding their superior ergonomics, a conservative clientele preferred a more conventional set up and modern Citroëns are fitted with the by now traditional stalks. |

|

|

• Faired-in rear wheels A commonly used styling motif was half-faired rear wheels; first seen on the 2CV and then on all subsequent models until the LN. This conveys an aerodynamic advantage since the turbulence caused by the rotation of the wheels is reduced. Furthermore, in an era when nearly all cars were rear wheel drive, it emphasised the front wheels and thereby emphasised the fact that the cars were front wheel drive. |

|

|

Many of the technologies invented or adapted or adopted by

Citroën have become mainstream but a much larger number have been

abandoned. Sometimes this is due to legislation and sometimes it

has been a matter of cost. Sometimes however, I suspect that

Peugeot has philosophical objections – especially when the Citroën

solution is easier and cheaper to implement than the conventional

alternative and proves to be more effective. |

|

| © 2016 Julian Marsh/Citroenet |

Parts of this article originally appeared in the Citroenian © Citroën Car Club 2014 |